Introduction

At issue in this case is pro se plaintiff Emilia Farrell's claim that Unit 2 of the 2-12th Street Condominium in Salisbury a Unit which she owns individually has an appurtenant right to park on defendant Janice Farrell's abutting property, a claim which Janice denies. [Note 1] The area in dispute is part of an express right of way over Janice's land which benefits both the Condominium parcel and other neighboring properties. Thus, to cover her bases, Emilia has also brought her claim in her capacity as a trustee of the 2-12th Street Condominium Trust which, pursuant to the Condominium Master Deed, owns whatever rights derive from that express easement. [Note 2] The parties have now cross-moved for summary judgment. [Note 3]

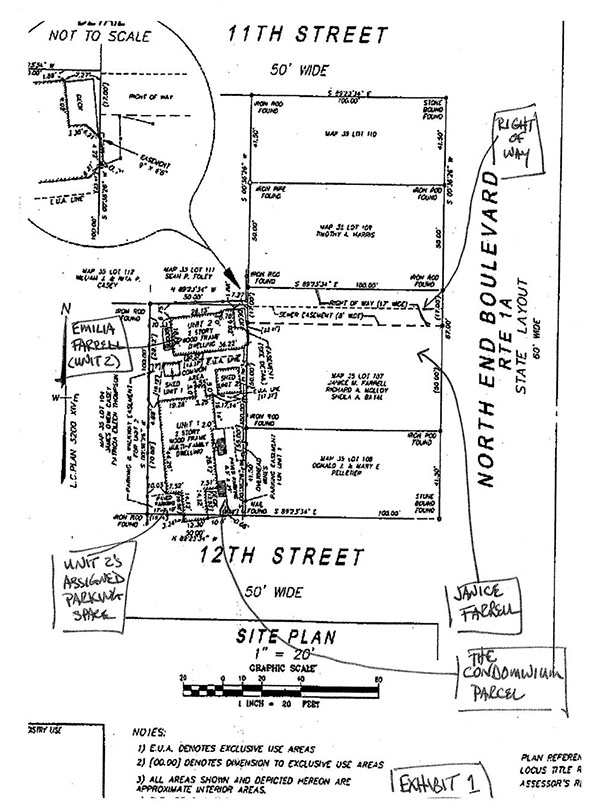

The Condominium parcel fronts on 12th Street West. See the Condominium Site Plan, a copy of which is attached as Ex. 1. Unit 2 (Emilia's) is the rear unit, with an assigned, exclusive parking space on the Condominium parcel located directly on 12th Street, and with a walkway easement over the Condominium land to that space. See Ex. 1. The right of way easement at issue in this case, 17' wide and 100' long, is on Janice's land and leads from North End Boulevard (Route 1A) across Janice's land to the rear of the Condominium parcel. See Ex. 1. As noted above, this right of way easement serves not only the Condominium parcel, but also the other properties it abuts, most notably the parcel immediately to the north of the Condominium's. See Ex. 1.

Emilia's claim of a right to park on Janice's property, in essence, is two-fold. The first is an argument that the express right of way across Janice's land includes a right to park on it, either by its specific language or by implication. Because this argument arises from the express right of way easement itself, and because the Condominium Trust holds all of those rights pursuant to its Master Deed, [Note 4] only the Condominium Trust can bring it. The second is a contention that, as a result of her past parking in the right of way area parking which she alleges has been continuous (either her or her tenants') since 1988 prescriptive rights appurtenant to Unit 2 have accrued. Since this parking occurred while Emilia owned and occupied Unit 2, she arguably can bring this claim individually. Whatever the basis of these parking claims, and whoever they belong to, Janice denies them, and she is correct to do so. None of them have merit.

As an initial matter, Emilia cannot bring claims belonging to the Condominium Trust pro se and, on that basis alone, those claims must be dismissed. As previously noted, all rights to the right of way were conveyed to the Condominium Trust in the Condominium Master Deed. As more fully discussed below, as a matter of law, a trust cannot be represented by a non-attorney, even if that person is a trustee.

Moreover, even if Emilia could bring those claims pro se, all of them fail. So do her individual prescription-based claims. On the undisputed facts, as a matter of law, the express right of way easement does not include a right to park, and Janice's land is registered, so no rights of adverse possession, easement by necessity, or prescriptive easement have or can accrue. G.L. c. 185, § 53. Accordingly, Janice's motion for summary judgment is ALLOWED, Emilia's cross- motion is DENIED, and Emilia's claims are DISMISSED in their entirety, with prejudice.

Facts

Summary judgment is appropriate when there are no genuine issues of material fact and, on those facts, the successful party is entitled to judgment as a matter of law. [Note 5] Targus Group Int'l, Inc. v. Sherman, et al., 76 Mass. App. Ct. 421 , 428 (2010); Mass. R. Civ. P. 56(c). The following facts are either undisputed or taken in the light most favorable to Emilia, the party against whom summary judgment is entered.

Emilia, individually, is the owner of Unit 2 of the 2-12th Street Condominium, located at 2-12th Street West in Salisbury. She is also a trustee of the Condominium Trust, which owns the parcel on which her Unit sits. Janice owns 433 North End Boulevard, a single family home which abuts the Condominium Trust parcel on its east. There is a 17'-wide by 100'-long right of way on Janice's land, benefiting both the Condominium Trust parcel and the other properties the right of way abuts, which leads from North End Boulevard (Route 1A) across Janice's property to the northeast corner of the Condominium parcel and the southeast corner of the parcel to the

Condominium's north. See Ex. 1. Both the Condominium Trust parcel and Janice's property are registered land.

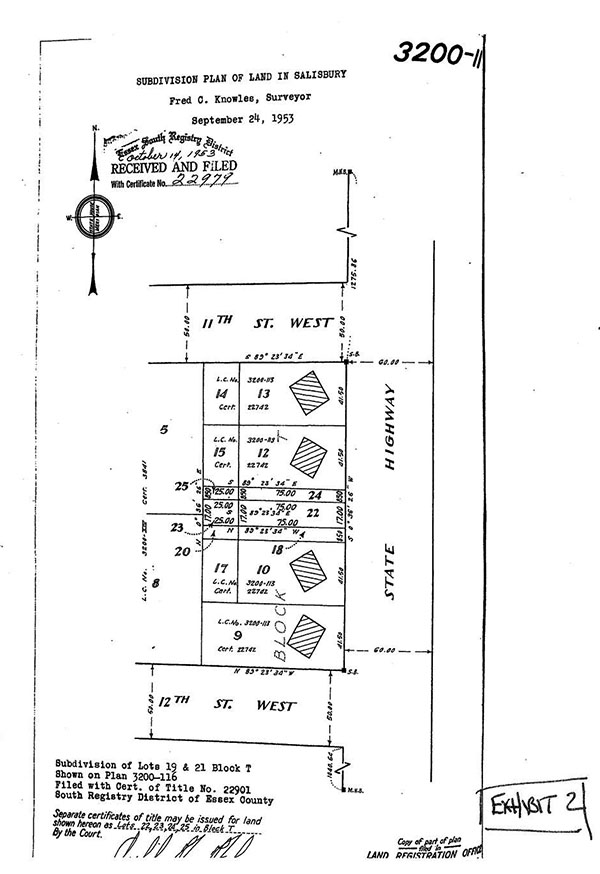

Janice's Certificate of Title reflects that her land (the burdened parcel) "is subject to a right of way in favor of lot 8 [the Condominium Trust parcel] as described in deed from Ruth J. Donahue to Thomas B. Farrell et ux, dated March 10, 1956 and filed as Document 78410 in said Registry." [Note 6] Mirroring that, the Certificate of Title for the Condominium Trust parcel (the benefited land) states that "[t]here is appurtenant to the above described land a right of way in a strip of land seventeen (17') feet wide shown as lots 22 and 23, Block T, on a plan filed with Certificate of Title #22979, as described in deed from Ruth J. Donahue to Thomas B. Farrell et ux, dated March 10, 1956, and filed as Document #78410 in said Registry." The Donahue to Farrell deed so referenced describes it as a "right of way over the 17-foot strip of land shown on Land Court plan No. 3200-117, as Lots 22 and 23." There is no mention in either Certificate, in any document on file at the Registry, or in any off-record title-related document whatsoever, of a right to park on the right of way, or on any part of it. It is described, solely and simply, as a "right of way."

Emilia began living in the building that is now Condominium Unit 2 in 1988 when she was still married to her ex-husband, and alleges that either she, her ex-husband (when they were married), or her tenants have continuously parked on the right of way in the area next to that Unit since that time. She was deeded what is now the Condominium Trust parcel in her divorce settlement and, in 2010, formed the Condominium Trust, conveying it both the parcel and the parcel's appurtenant rights in the right of way at that time. [Note 7] The Condominium has two units (Unit 1 at the front and Unit 2 at rear) and the Condominium documents created separate, on-site parking areas for both of them, both directly on 12th Street (see Ex. 1). Emilia subsequently sold Unit 1 to a third-party purchaser.

The Condominium site plan (Ex. 1), created by Emilia, [Note 8] makes no claim to a parking space on the right of way, and shows none. She has kept Unit 2, either living there herself as a second home or renting it to tenants, and now wants to sell it. Janice has not objected to Emilia's parking on the right of way in the past indeed, on several occasions, she has given Emilia express permission to do so but Janice is adamantly opposed to Emilia's claim of a "right" to such parking and, thereafter, the sale of that right to a stranger. Janice contends that all of Emilia's past parking has been with Janice's permission but, for purposes of this motion, will consider it to have been adverse.

Further facts are set forth in the Analysis section below.

Analysis

Because the Condominium Parcel is Owned by a Trust, Emilia, a Non-Attorney, Cannot Bring Any Claims Belonging to the Trust Pro Se

"'[T]he commencement and prosecution for another of legal proceedings in court, and the advocacy for another of a cause before a court . . . are reserved exclusively for members of the bar.'" LAS Collection Mgt. v. Pagan, 447 Mass. 847 , 849-850 (2006), quoting Lowell Bar Ass'n v. Loeb, 315 Mass. 176 , 183 (1943). Except in small claims actions, "corporations must appear and be represented in court, if at all, by attorney." Varney Enter., Inc. v. WMF, Inc., 402 Mass. 79 , 82 (1988). The same rule applies to trusts, including real estate trusts. See Kitras v. Zoning Adm'r of Aquinnah, 453 Mass. 245 , 250 n. 14 (2009); Eresian v. Mantalvanos, 94 Mass. App. Ct. 1106 , 2018 WL 5116572 at *1 n. 4 (Oct. 22, 2018) (Mem. & Order Pursuant to Rule 1:28), citing Kitras, 453 Mass. at 250 n.14. Non-attorneys cannot represent trusts in court, pro se, even if they are trustees of that trust. Id.

Neither Emilia individually, nor her individually-owned Unit, have any rights arising from the express right of way easement, i.e. those granted by its specific language or which can be implied from the grant. That express easement benefits the Condominium Trust parcel, and all of those rights were deeded to the Condominium Trust in the Condominium Master Deed, which now owns them. Emilia may be a trustee of that Trust, but she is not an attorney. She is thus barred from bringing this action on behalf of the Trust pro se, and any claim belonging to the Trust must be dismissed for that reason alone. Id. These include all of the arguments she asserts, with the possible exception of her claim of a prescriptive easement appurtenant to Unit 2 arising from its occupants' past parking in the right of way. For completeness sake however, as the Trust's claims would be dismissed even were it represented by counsel, I address the merits of those arguments, as well as Emilia's prescriptive claims, below.

The "Right of Way" Easement Does Not Include a Right to Park

The Condominium Trust and the other neighboring property owners have an express easement in the 17' x 100' right of way. As noted above, that easement is described in the Condominium's Certificate of Title and in Janice's Certificate of Title as "a right of way," and in the source deed that created it as "a right of way over the 17-foot [wide] strip of land shown on Land Court plan No. 3200-117, as Lots 22 and 23" (emphasis added). There is no mention on either the deed or the Certificates of any right to park. Thus, it is only a right to pass and repass and does not create or imply a right to park except for temporary stops incident to travel. See generally Opinion of the Justices, 297 Mass. 559 , 562 (1937) (right to pass and repass does not include right to park except temporary stops incident to travel); Harrison-Beauregard v. DeNadal, Mem. & Order Pursuant to Rule 1:28, 71 Mass. App. Ct. 1107 , 2008 WL 282471 at *1 (Feb. 1, 2008) (same, citing Opinion of the Justices). Contrast Harrington v. Lamarque, 42 Mass. App. Ct. 371 (1997), where a right to park could potentially be implied from the physical characteristics of the way in the location of the claimed easement (it was wider than the other parts), a right to park was "reasonably necessary" for enjoyment of the express right to use the beach, which was otherwise too far away from the residences, and there was contemporaneous evidence showing intent to create a parking easement. None of those circumstances exist here. The easement provides access to other properties besides the Condominium Trust parcel, including the parcel immediately next to where Emilia wants the right to park, and thus should remain unblocked; a right to park in that location is not "reasonably necessary" because Emilia's Unit has an assigned parking space on the Condominium Trust parcel itself, in a location she herself chose when she created the Condominium; the area at issue is registered land, in which easements by necessity or arising by prescriptive easement are explicitly barred, G.L. c. 185, § 53; and there is no title-related documentary evidence, on or off-record, which reflects a right to park or an intent to create one by the grantors of the easement.

Emilia's argument that a right to park a single car immediately next to her Unit can be implied because such parking, she alleges, still leaves sufficient room for cars accessing those other properties to get around it fails as a matter of law. See Delconte v. Salloum, 336 Mass. 184 , 189 (1957) (holding that private way must be left unobstructed by parked cars and that "[t]he fact that there still remains room for vehicles to pass and repass to the beach does not render the habitual parking of vehicles on this private way any less a nuisance to the defendant"). Her further argument that a right to park can be implied from the fact that the right of way terminates at the edge of her building, making vehicular access onto the Condominium Trust property impossible, also fails. The easement serves other properties that have a right to keep it unblocked (see Delconte, supra) and, even without the ability to drive from it onto the Condominium Trust property, its purpose is not frustrated. It provides unrestricted pedestrian access, and also vehicular access with the right to stop temporarily to load and unload passengers, groceries, and the like.

Most tellingly, the easement is on registered land. The general rule, surely known to the drafters of the easement, is that rights to pass and repass do not include a right to park except for temporary stops incident to travel (see Harrison-Beauregard, 2008 WL 282471 at *1), and the fact that a right to park was not explicitly included in the grant indicates that no such right was intended. Moreover, as Land Court Plan 3200-117 (Ex. 2) indicates, the easement was created before the Unit 2 building was built (unlike others, it does not appear on that plan). Had vehicular access onto the Condominium property been deemed essential to its purpose, that building would have been located elsewhere or constructed in such a way that cars could get by it. And had parking on the right of way been deemed essential, it would have been included in the easement language.

Emilia has No Right to Park on Janice's Land through Prescriptive Easement, Adverse Possession, or Easement by Necessity

Registered land was created for the purpose of ensuring "that holders of land registered under the act enjoy certainty of title to their property." Hickey v. Pathways Ass'n, Inc., 472 Mass. 735 , 754 (2015) (internal citations omitted). Judgments of registration "'shall set forth the estate of the owner and . . . all particular estates, mortgages, easement, liens, attachments and other encumbrances . . . to which the land or the owner's estate is subject.'" Id., quoting G.L. c. 185, § 47. "'[E]very plaintiff receiving a certificate of title in pursuance of a judgment of registration, and every subsequent purchaser of registered land taking a certificate of title for value and in good faith, shall hold the same free from all encumbrances except those noted on the certificate, and any of the [statutorily enumerated] encumbrances which may be existing. . .'" Hickey, 472 Mass. at 754, quoting G.L. c. 185, § 46. Registered land "is protected to a greater extent than other land from unrecorded and unregistered liens, prescriptive rights, encumbrances, and other burdens." Peters v. Archambault, 361 Mass. 91 , 93 (1972) (internal citations omitted). Both Emilia's land and Janice's are registered, and the parking spot at issue is on Janice's registered land.

G.L. c. 185, § 53 specifically states that "[n]o title to registered land, or easement or other right therein, in derogation of the title of the registered owner, shall be acquired by prescription or adverse possession. Nor shall a right of way by necessity be implied under a conveyance of registered land." Hickey, 472 Mass. at 755, quoting G.L. c. 185, § 53; see also Brown v. Kalicki, 90 Mass. App. Ct. 534 , 539-540 (2016) (holding plaintiffs' beach area entitled to protection afforded by registration and thus not subject to prescriptive easement); Gifford v. Otis, 70 Mass. App. Ct. 211 , 215 (2007) (denying prescriptive easement claims because prescription rights were interrupted when land was registered); Goldstein v. Beal, 317 Mass. 750 , 757 (1945) (denying prescriptive easement and adverse possession claims over fire escape which extended three feet nine inches onto registered land); Bradley v. Stonecroft Properties Inc., Mem. & Order Pursuant to Rule 1:28, 78 Mass. App. Ct. 1109 , 2010 WL 4628743 (Nov. 17, 2010) (denying plaintiff's easement by implication and easement by necessity claims over registered land); Bokhour v. Fronk, 2007 WL 949640 at *8 (Mass. Land Ct., Mar. 30, 2007) (denying easement by necessity over registered land).

For Emilia to have a right to park on the easement, it would have to be included in the express easement rights as they appear on the certificates of title or someplace else in the registered land system. See Jackson v. Knott, 418 Mass. 704 , 710 (1994). It does not. As previously discussed, it is not included in the Condominium parcel's express rights, which are confined to use of the easement as a "right of way", i.e. to pass and repass only. See Opinion of the Justices, 297 Mass. at 562; Delconte, 336 Mass. at 189; Harrison-Beauregard, 2008 WL 282471 at *1. At best, Emilia has only a right to temporarily stop there, for example, to load and unload passengers, groceries, packages, or pick up the trash. Id.

There are only two exceptions to the requirement that the right claimed appear on the face of the certificate of title. See Jackson, 418 Mass. at 710-711. "If an easement is not expressly described on a certificate of title, an owner, in limited situations, might take his property subject to an easement at the time of purchase: (1) if there were facts described on his certificate of title which would prompt a reasonable purchaser to investigate further other certificates of title, documents, or plans in the registration system; or (2) if the purchaser has actual knowledge of a prior unregistered interest." Id. at 711 (internal citations omitted). Emilia's claim does not fall within either of these exceptions.

The first exception provides that a registered landholder might take the land subject to an easement if the certificate of title contained something which prompted the person to further investigate "other certificates of title, documents or plans in the registration system." Id. (emphasis added). This does not apply because nowhere on any prior registered deed, plan, or certificate of title is there a grant to Emilia or the Condominium parcel of a right to park on the easement. All that exists is the right to use it as a "right of way."

The second exception provides that a registered landowner takes property subject to an encumbrance if he or she "acquired title with actual knowledge of a prior unregistered interest" Jackson, 418 Mass. at 713. But this would have to be knowledge of an actual grant. Merely observing such use is not sufficient. See Calci v. Reitano, 66 Mass. App. Ct. 245 , 248-250 (2006) (holding that neighbor's attempt to establish easement over registered land pursuant to the "actual notice exception" was unsuccessful because "it is not enough that the holder of registered title know that the land has been used in a certain way that might indicate an easement, because this could be merely a permissive or perhaps adverse use, which specifically does not give right to an easement under G.L. c. 185, § 53"); see also Commonwealth Elec. Co. v. MacCardell, 450 Mass. 48 , 52 (2007) (in order "[t]o fulfill the actual notice exception to a recorded easement, it is not enough that the holder of registered title know that the land has been used in a . . . way that might indicate an easement because this could be . . . [either] adverse use, which is not allowed under G.L. c. 185, § 53, or permissive use" (internal citations and quotations omitted)).

Janice had no "actual knowledge" of Emilia or the Condominium Trust parcel having a granted easement right to park on Janice's land because there was no such grant, and Emilia has not produced one. Although Janice was aware that Emilia parked at the end of the easement near her unit, and gave her verbal permission to do so on multiple occasions, this does not satisfy the "actual knowledge" standard as described above. This standard requires that there be notice to the registered land owner that the other person had a granted easement over the land, and here there was no such grant, and no such notice of a grant.

Parking on Janice's Land is Not a De Minimis Encroachment Allowing Emilia the Right to Do So

"In Massachusetts a landowner is ordinarily entitled to mandatory equitable relief to compel removal of a structure significantly encroaching on his land, even though the encroachment was unintentional or negligent and the cost of removal is substantial in comparison to any injury suffered by the owners of the lot upon which the encroachment has taken place."

Peters v. Archambault, 361 Mass. 91 , 92 (1972) (internal citations omitted). De minimis encroachment refers to instances when an "encroachment is trivial, or de minimis, in nature." Capodilupo v. Vozzella, 46 Mass. App. Ct. 224 , 226 (1999) (internal citation and quotation omitted). "[E]quitable exceptions to the mandatory removal rule have [almost] never been applied to registered land. . . [but] courts have acknowledged the possibility that the exceptions might apply in appropriate instances." Id. at 228 (internal citations omitted) (finding that an encroachment of at most 4.8 inches on registered land into an open court yard where trash was stored was de minimis). No such exception applies here.

First, a parked car is not de minimis. Second, even if it was, case law allowing encroachments to remain typically involve a structure or permanent building. See id. at 225 (encroachment of one-story structure onto plaintiff's property); see also Peters, 361 Mass. at 92 (encroachment of house built partly on neighbor's lot), Brandao v. DoCanto, 80 Mass. App. Ct. 151 , 153 (2011) (encroachment of condominium unit), Calci v. Reitano, 66 Mass. App. Ct. 245 , 251-252 (2006) (encroachment of second-story porch and utilities was not de minimis). Such encroachments do not include non-structural uses, such as easily-moved cars, unless prescriptive rights have accrued. And, as noted above, no such prescriptive rights accrue against registered land.

Emilia's Other Arguments

Emilia makes a series of additional arguments as to why she should be allowed to park on the right of way, including laches, easement by implication, easement by estoppel, and merger, all of which lack merit.

Laches

Laches is an equitable doctrine which bars "unreasonable delay" in litigation. A.W. Chesterton Co. v. Massachusetts Insurers Insolvency Fund, 445 Mass. 502 , 517 (2005). It is generally "a question of fact for the judge." Id. However, "[l]aches is not mere delay, but delay that works disadvantage to another." Id. (internal quotation and citation omitted).

Here, laches cannot apply because, among other reasons, Emilia has not been prejudiced. Because the land is registered, no rights accrue with time.

Easement by Estoppel

In Massachusetts, "general estoppel principles

do not apply to the formation of easements." Blue View Const., Inc. v. Town of Franklin, 70 Mass. App. Ct. 345 , 355 (2007). "Cases recognizing that an easement may be created by estoppel have fallen into two general categories." Patel v. Planning Bd. of North Andover, 27 Mass. App. Ct. 477 , 481 (1989). First, "'when a grantor conveys land bounded on a street or way, he and those claiming under him are estopped to deny the existence of such street or way, and the right thus acquired by the grantee (an easement of way) is not only coextensive with the land conveyed, but embraces the entire length of the way, as it is then laid out or clearly indicated and prescribed.'" Id., quoting Casella v. Sneirson, 325 Mass. 85 , 89 (1949). The second category arises "'where land situated on a street is conveyed according to a recorded plan on which the street is shown, [and] the grantor and those claiming under him are [thus] estopped to deny the existence of the street for the entire distance as shown on the plan.'" Patel, 27 Mass. App. Ct. at 482, quoting Goldstein, 317 Mass. at 755. Courts have refused to broaden this rule, stating "[w]e are aware of no case in Massachusetts recognizing the creation of an easement on broader principles of estoppel [than the two categories described above]." Blue View Const., Inc., 70 Mass. App. Ct. at 355 (internal quotation and citation omitted); see also Ballo v. Cushing Street, LLC, 2008 WL 802498, at *10 (Mass. Land Ct., Mar. 27, 2008) (holding that "[p]laintiff's claim to access a parking space is entirely different than either of the two principles set forth by prior Massachusetts jurisprudence," and refusing to expand easement by estoppel principles to include plaintiff's claim to access the parking space). Thus, as Emilia's claim of a right to park on the easement does not fall within either of these two categories, there is no easement by estoppel.

Merger

Emilia's final argument is based on "merger". There is no such argument, however, because the "merger" that occurred extinguishing the easement rights of certain parcels benefited by the easement when Janice acquired them did not affect the Condominium Trust parcel, which was never merged. Moreover, merger does not create easements, it extinguishes them. Whatever merger occurred on land now owned by Janice could not, and did not, affect or modify the Condominium Trust parcel's easement rights. They remain the same and, as discussed above, do not include a right to park. [Note 9]

Conclusion

For the reasons set forth above, Janice's motion for summary judgment is ALLOWED and Emilia's cross-motion is DENIED. Emilia's claims of an appurtenant right to park on the right of way across Janice's land are DISMISSED in their entirety, WITH PREJUDICE.

Judgment shall enter accordingly.

SO ORDERED.

EMILIA FARRELL, individually and as trustee of the 2-12th Street Condominium Trust, v. JANICE FARRELL.

EMILIA FARRELL, individually and as trustee of the 2-12th Street Condominium Trust, v. JANICE FARRELL.